The Simple Machine Model

To develop a shared strategic perspective, it’s important to articulate both a plan for what we’re trying to do and a narrative of what we’ve done. This allows us to work together to refine our specific organizational perspective and share it with others, outside of the Center for Especifismo Studies (CES), in the form of writings, discussion groups, and public seminars.

We begin with the inclusion of this internal strategy document:

A. “de la nada”, sin historia ni ideología

B. con militancia política adentro de un ciclo estricto

C. entre dos modos sociales en el mismo ciclo

D. en una dinámica política que permite varias combinaciones estratégicas para conectar lo social y lo político

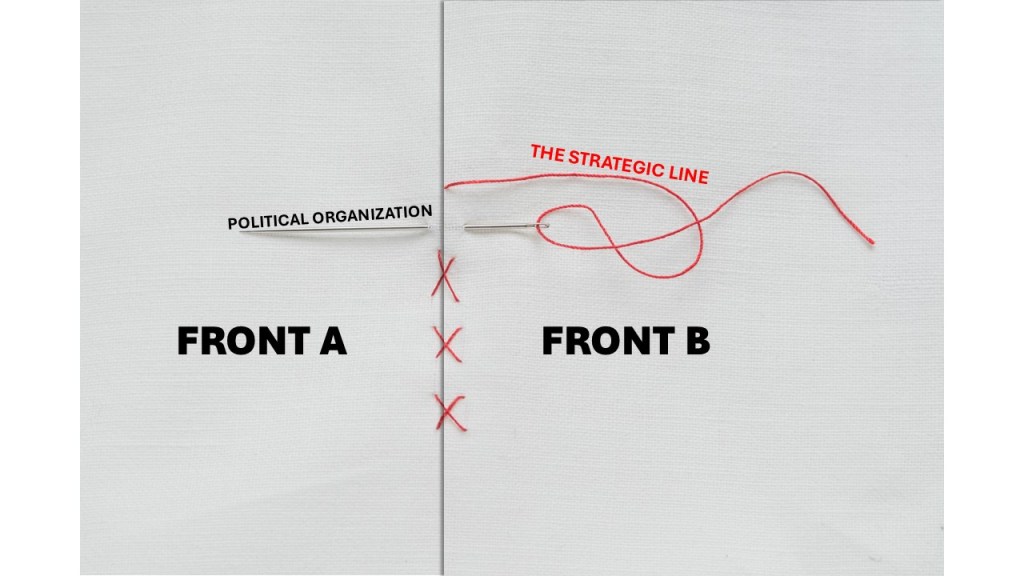

• On the social level (in red), everyone has the potential to participate and “push the cycle” to continue. This is the basis of social force. It can always be organized more efficiently and with more people, but since it isn’t ideologically specific, social force doesn’t have to be subordinate to the political level (in black). However, this also means that the political decisions of a movement are not always influenced by the rank-and-file participants.

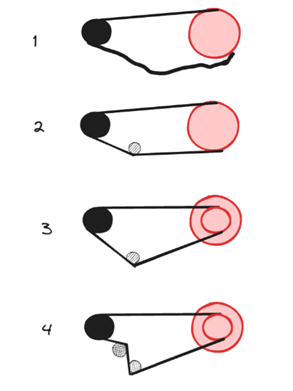

• A small motor is a good metaphor to understand a revolutionary political strategy that isn’t vanguardist, but a motor assumes the smooth functioning of basic mechanisms. Today, in regard to organizing culture, this assumption is wrong. Bicycles, with their gears, chains, and exposed shifting, offer a simple machine model that is a more useful didactic tool.

• Without a mechanism for adding tension, the political level is only loosely influenced by the social level and depends on the connecting mechanism to keep itself from coming loose, despite the inevitable bumps and fluctuations. When this connection is lost, when the “chain” falls off, the two levels become disengaged and mass movements come to a stop.

• If the social demands are high but the political influence is low, then a cycle of struggle requires too much force to sustain for very long. So, the concept of “gears” allows us to strategize around various combinations of social-level demands and political-level influence.

The Political Organization:

1. front-line work: immediate forms of participation on the social level that are independent from the political cycle, but that have no way of influencing the decision-making on the political level

2. rear-guard work: consistent tension on the political cycle of the movement, preventing anarchist disengagement and allowing others to come in contact with the political organization

3. two modes: a “pivoting and springing” dynamic that can stay connected to the social level as it oscillates between modes (bigger/smaller, mobilizing/meeting, conflict/recovery, motivation/burnout, summer/winter, public/clandestine, local/remote) 4. coordinated gears: influence on the political level through multiple combinations of modes, forms, and techniques of social insertion

If the conditions change, the priorities and strategic line need to change

When lots of different people are involved in real struggles on the social level, but their paths aren’t connected, this is a problem. Their work isn’t strategic because it isn’t an organized struggle reaching beyond its immediate environment. At the level of society, we can’t exclude anyone, especially not within a revolutionary project that has to be popular and requires large-scale participation. Since a revolutionary project consists of more than one major event, building Popular Power means constant movement forward. This kind of movement within a broader project requires militants to be organized in a specific organization.

The path that a specific organization follows has to be related to the conditions of a more or less stable general situation, but when there is no way forward, another one must be fought for and produced through struggle.

Another way to say this is that a political organization has to project itself into the future if it wants to be effective. As long as things are mostly the same, this projection is useful and can be effective. If things change drastically, the way of projecting itself into the future has to change as well.

It can be difficult to determine what counts as a relevant factor in a situation. So, we have to regularly ask ourselves if we’re missing any important perspectives in our strategic planning. Through conjunctural analysis, a revolutionary organization can better understand the political climate, which is characterized by the degree of popular support and the strength of reactionary forces. It’s also important to remember that a situation looks different to one organization than it does to another, raising two more questions: what is a strategic point of view, and where would it ideally be positioned?

The specific path for working together with dangerous forces in society is complicated and uncertain. There won’t be a single way of dealing with these issues. This points back to the need for organizational unity and ideological commitment, to know what we’re fighting for and why we’re fighting. Still, without consistent militant organizing, we sometimes have to start from zero, which can make this all seem very idealistic and not necessarily applicable. It’s hard to see past the most basic and immediate needs. This is why the strategic line needs to take these needs into account.

How do we deal with the inevitable zigzagging?

We know from experience that popular mobilizations can be stopped. They don’t just survive and continue on their own. To keep them going, we need to be ready to take risks and be responsible for their consequences. This is what we call militancy. The oppressed classes must have the independence to create their own path and the militant commitment to follow that path through a multitude of shortcomings, unforeseen problems, personal and organizational conflicts, crises, repression, etc.

What we’re saying is that the class struggle is messy. With its ideological pluralism and lack of organization, it’s equally as complex as the social forces shaping the current conjuncture. Currently a revolutionary movement is not one of these forces, to say nothing of the weak position of anarchism today. It’s true that, as anarchists, we may be well anchored in place, at stations in the struggle (unions, study groups, community assemblies, co-ops, mutual aid collectives, etc.). However, this also means that we’re often irrelevant to social movements more broadly since we’re sometimes too stuck in place to be part of advancing the class struggle. Especifismo militants want anarchists to be immediately recognized as comrades in the revolutionary project, as militants headed down the same road of struggles, even if we have a different zigzagging pattern.

This is related to our discussions about militant style. Obviously, since especifismo militants are active participants in the class struggle, their militant formation consists of more than just posing in the mirror and putting on labels found online. Militant style is not a final product or a glossy presentation. It consists of daily tasks that have a strategic direction. These tasks can’t be done alone, and they can’t be done by following old habits and dogmatic ways of doing things. And, maybe most importantly of all, the militant style we’re describing can’t be developed by ridiculing people and only ever getting frustrated with them.

Like the class struggle more broadly, developing revolutionary strategy is a messy process of learning, and not always looking good doing it. Militants have the daily task of participating in the class struggle from within the system, not from outside, and with the people, not against them or only by criticizing them. This project must be taken to heart by the militants, and it must point toward the final objective of libertarian socialism.

We have to ensure that our activities are contributing to the revolutionary project. This means staying connected to and attuned to the concerns and urgencies of the community, not arguing from a removed position or an outside perspective, not claiming an enlightened point of view. This relates to the basis for the “North American Anarchist Primer”. It’s about our responsibility to speak from somewhere at some time. While the Center for Especifismo Studies (CES) is an international organization with participants and supporters on multiple continents around the world, to make this manual as practical as possible, it has been written with the North American English-speaking anarchist revolutionary as the assumed reader. This doesn’t prevent people in other contexts or coming out of other tendencies from learning, using, transforming, or elaborating on the especifismo theory articulated in this text. But it does explicitly force them to adapt it to their local and regional contexts. Even in our own local contexts, we will have to work to make this theory relevant to our own communities and social-level militancy.

Staying attuned to the struggles of the people is an ethical principle of anarchism. This is why we criticize authoritarians and self-proclaimed vanguards who ignore the reality of how class struggle is taking shape today. This current manifestation of class society splits the oppressed classes across multiple different fronts, so it would be wrong to see zigzagging tactics as inherently problematic. We think the various daily tasks of militants require them to zigzag in response to current conditions. For us, this pattern of movement is a way of advancing toward a point of rupture with the capitalist system, while not getting stuck at just one station, repeating the deployment of just one tactic. We don’t want to spend our energy only on defensive measures. We want to make gains. We want to push forward. We want to win.

A revolutionary movement’s success is based on its potential for coordination and organization. It will take multiple steps in succession to create a popular organization capable of confronting reactionary forces, of surviving a revolutionary moment, and of establishing a libertarian socialist society. This means that mutual aid collectives, unions, and assemblies are zigs (or zags depending on the context), but we don’t want their influence to be stuck in one place. Just like how we don’t want the revolutionary movement to be stuck in one place either.

A new kind of protagonism

Though we’ve discussed the limitations of metaphors, especially as they relate to gardens as fabricated “settlements”, whether because of their potential to be interpreted as colonialist or vanguardist, we still see a use for the image of cracks appearing in the system, sprawling outward, ready to be filled with soil and plants that will also be sprawling as they take root.

This metaphor helps us understand what is meant by words like conjuncture, context, and situation. Reality is experienced as a situation, so when people’s needs are met, their experience of a situation is very different. We’ve discussed a connection between this plurality of experiences and the utopian objectives of the Zapatistas who say they want a world “where many worlds fit”.

How can different people, living within the same system, but with different experiences of that system, coincide and interact in strategic ways?

Different realities produce different experiences, and from our militancy, we know that some experiences are repeatedly discounted. This can be a persistent problem for an organization. After our discussions on strategy, we see a need to factor in a plurality of perspectives when conceiving of a strategic line because it’s a mistake to think that there’s only valid information coming from one front of struggle.

Racism, xenophobia, misogyny, etc. are persistent forces acting against the political solidarity of the oppressed classes. They serve as built-in defense mechanisms protecting the system. When these forces have more influence in society, the system doesn’t need to respond directly. This is why a revolutionary project is aimed at these destructuring cracks that are already forming at multiple points in class society. These “protagonist nodes” create opportunities for the production of a new strategically relevant perspective.

Here, it’s important to point out that a historical subject is not just a single individual or stereotype. The protagonism of social revolution is a collective form of leadership, so it’s centered on the popular organization as a whole. This means that while individually we may be experiencing dissonance, collectively there’s still potential for the production of a new kind of outlook based on the popular organization of society. This is what we mean when we talk about “a strategy of building Popular Power”; it’s based on the potential force of our cooperation over time. So, after a dissonant experience or a period of crisis, taking time to reflect collectively can strengthen our militant commitment, as well as our strategic unity.

At the Center for Especifismo Studies (CES), our conception of the historical subject of the social revolution is broader than the economic sphere. For us, the popular organization of the dominated and oppressed classes specifically includes those who have nothing, those who are deprived of almost everything, and those who have access to very little. Today, most people live in conditions that don’t give them access to most of what they need. The situation is made worse because the capitalist system and the State provide alternative routes that lead people away from politics as a form of direct action and toward the mass consumption of politics as a spectator sport, meaning a kind of entertainment. Representational democracy and the entertainment industry are both ways of taking our discontent, packaging it, and selling it back to us.

Different from what’s produced by the immediate situation, and different from what’s reproduced by the system

Even though it’s the product of an antagonistic reality, strategy has the potential to produce a new and collectively shared perspective. We see it as a path out of an antagonistic situation. Revolutionary strategy has to make sense and be consistent enough to follow even as the situation evolves. It must be sustainable and coherent to effectively hold things together and “prevent unraveling”.

Since the objective is to build Popular Power as it progresses, revolutionary action should be based on things as they are, not as we prefer them to be. If we only focus on what we like or what we want to see, we won’t build a social force capable of producing and defending a rupture with the system. To do this, we need a strategic line out of this antagonistic scenario and toward something more ideal. This requires us to take into account many different perspectives and unify them around a sustainable path forward.

On the social level, plurality is necessary and desirable, but on the political level, a shared strategic path forward won’t be produced by just amassing the magic number of individuals. A political organization is defined by its ability to analyze and strategize out of a conjuncture. So, the starting point for a political organization is the initial conjuncture, but as the process continues, other historical conjunctures will also have to be dealt with and overcome. As we’ve said before, a revolutionary process is political, not personal. So, it shouldn’t be centered around some leader or group that claims to have perfectly mapped out the situation or to be the only one to see the correct path forward. The strategic line of a political organization isn’t produced by the “independent mental processes” of an enlightened individual because it’s not a “hot take” from the internet. Those kinds of personally conceived paths forward are less complex and dynamic than political strategy because they arrive at conclusions from an individual perspective rather than an organizational perspective.

Producing reality through a process of rupture

Relevant discourse is the result of actively coordinating and working together. It consists of what makes strategic sense in a certain context combined with what’s related to it but is articulated and expressed outside of the immediate situation. This means that it’s a connection between the strategic line, the analysis of the situation, and the manifestation of this understanding in the wider peripheries of struggle.

In our Second Grade discussions at the Center for Especifismo Studies (CES), we’ve come to understand discourse-practice as the connection between theory and action, the unity between means and ends. A consistent discourse-practice helps to resolve theoretical problems between short and long-term objectives, as well as between ideology and tactics.

It’s also important to explain what we mean when we talk about “a process of rupture”. It refers to a series of movements and events aimed at destructuring the system and establishing a new popular organization of society that we call libertarian socialism. This concept is related to strategy and to political organization because it orients the revolutionary project toward direct confrontation and struggle with the forces of capital. To put it another way: we don’t think it’s enough for us to only change ourselves personally, locally, or culturally. This leads us to the conclusion that a liberatory social force is the capacity to make a strategic discourse into a reality, to act strategically in a way that makes sense to others. We see social force as the potential for carrying out the revolutionary project to its intended goal. This requires planning, acting, and reflecting in a productive and progressing way that nurtures the momentum of social movements.

Political organization: how, why, and to what ends

Let’s now quote from Gustave:

“We have to focus our reflections on concrete needs we have because, if we don’t clearly name the needs, a specific organization risks becoming a depoliticizing, essentializing and time-consuming space. From the practices of autonomy in feminist movements, we can identify four axes: discursive, personal, organizational, programmatic. These four axes help to better define the needs that our practice will meet in terms of a specific organization.

The discursive axis is about the power of reappropriating language in order to redefine oneself with a non-sexist discourse.

The personal axis comes out of practices in self-awareness or discussion groups, in which participants share personal experiences of everyday sexism or violence in order to develop a common understanding of oppression and create support. The Italian separatist group Rivolta Femminile was in this direction and saw in this practice of sharing as an opportunity to awaken, in women, the self-consciousness necessary to become autonomous political subjects distinct from men. It was also a strategy of Mujeres Libres who used talking circles to “[normalize] women hearing the sound of their own voices in public” so they could gain confidence and participate more fully in political action.

The organizational axis implies organizing politically without cis men to use the absence of sexist behaviors and words to gain more freedom and efficiency in decision-making. The example of the Hyenas in Petticoats, which militated, among other things, against the sexism of the Liberal government’s austerity measures, was in line with this organizational axis: they had determined that feminist demonstrations were less likely to be usurped by a horde of cis men who believed themselves more capable of taking blows in front of the police. In the current context, a smaller group might decide to organize itself in a specific way without cis men, carving out space to acquire the necessary skill for speaking in public and debating with their peers, like in the context of a meeting for example. Back in the larger mixed space, this could weaken the stronghold that cis men usually occupy in political organizations, as well as the power they implicitly tend to hold in these kinds of spaces.

Finally, the programmatic axis is about developing plans for changes in social relations as well as the means to make these changes a reality. The various autonomous structures created by women in the Kurdish liberation movement are good examples of this programmatic axis: the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) were founded in 2013, composed exclusively of armed women fighting against the Syrian forces, Daesh and the fascist Turkish state. The aim of the YPJ is to work for the protection of women. For Kurdish women, there’s not only armed struggle, security patrols and women’s academies, but also a women’s village (Jinwar) and even a television channel. They organize themselves this way to avoid limiting themselves to only demanding equality or an improvement in the status of women, “asking a fundamental question: what would the world be like today if women had not been oppressed?” – hence their strong programmatic character. Women’s autonomy in the Kurdish liberation struggle is seen as a creative force for imagining a world where no one is oppressed. For them, organizing autonomously is an essential practice that allows them to build the confidence and solidarity necessary to destroy the patriarchal structures that are present not only among their enemies but also within their own mixed revolutionary political organizations, in which they are also very active. The women’s struggle is understood as inseparable from the broader struggle for the liberation of the Kurdish people and all oppressed peoples. In our context, from within a larger group, we could decide to organize ourselves specifically without cis men to discuss the dynamics we’re experiencing and find solutions to propose in a unified way to the rest of the mixed group.” [See: “Driving Tractors with your Gal Pals” Specific Organization: how why and to what ends by Gustave]

The difference between comrades and enemies might seem obvious, but in practice it’s never as clear as it is in theory

Sectarianism is a recurring problem in our movements. Sometimes it comes from prioritizing efficiency and constant progress, but it’s also the result of militants who are dogmatic about their organization’s program. They can’t see the situation in front of them and are quick to look suspiciously at anyone else working on a different political program.

For example, some political organizations defend an ideological (dogmatic) definition of friends and enemies. For them, it’s a constant distinction made between social classes, not necessarily between political actors, social movements, or mass organizations on the ground, in real life. These kinds of orgs don’t use an analysis of the conjuncture to determine who they can work with at a given moment, so they’re less flexible organizationally to move between different fronts of struggle where the distinction between friend and enemy might be made using different methods or based on different experiences.

We have to consider more than just what people believe; we have to consider what they do.

On top of that, only ever talking about the new society at the end of the road of struggle isn’t a good basis for gaining comrades today. It’s likely to result in seeing everyone as an irredeemable enemy. If we’re too idealistic, if we prioritize our utopian visions over the reality of today, we’ll incorrectly conclude that anyone who doesn’t share our final objectives for an ideal society is ignorant, unenlightened, or a class traitor. We’ll also make this mistake if we prioritize constant progress toward revolution at a rapid and steady pace. These shortcuts will not lead our movements down the most strategic path and will risk making enemies out of potential comrades. The capture of revolutionary militants by reformist movements and “big tent” political organizations often leads people inside and outside of these movements to see each other as enemies. Being too reactive about a political project happening right now can easily devolve into a sectarian dead-end. This only distracts from the political organizing and social work that especifismo militants are trying to realize over the long term.

Without a consistent revolutionary theory, tactics and strategy are easily confused

We see revolutionary militants as having the confusing task of being both rigid (ideologically) and flexible (tactically), so we consider strategy to be a way of navigating this contradiction collectively, instead of on our own.

We understand strategy as a framework with a specific content. It makes general guidelines within a broad context. These are parameters for action at different fronts and between different camps. This is why strategy, for us, is fundamentally about coordination over time.

Tactics, by contrast, are the steps toward the realization of strategy. In especifismo, this “zigzagging” is understood from within a strategic framework. In this way, tactics are subordinate to strategy because only strategy can sketch out a project for change. However, it’s always through tactics that we make strategy a reality and not just an abstract plan. So, the application of tactics needs to be flexible and able to change depending on the situation which points back to strategy again, as a relevant map of the situation and as the best way of inserting our long-term objectives into the current situation.

To be more concise, only tactics and objectives that fit within a strategic framework are relevant to a revolutionary project. If our tactics and our final objectives don’t fit into the current context, not only will they be ineffective, but they won’t even be understood as part of the larger project.

Talking about tactics isn’t enough, strategy shouldn’t be seen as a threat

Let’s now quote from the I-5AF:

“Our position is that organizational dualism must be practiced in order to maintain and develop an anarchist strategy and political line that is applicable to a variety of situations and can adapt as contexts change. Militancy like this requires the grouping together of an active minority that is interested in developing a common political program, a program built on trust, ethics, and revolutionary objectives. It is about putting everyone on the same page strategically in order to progress the political line.

The social level is more popular and massive than the political level. It is a pluralistic environment that can wash out, dilute, and co-opt revolutionary movements. On the social level, only the most organized and well defined political tendencies are distinct. Everything else can start to seem the same. Taking this into account, Tommy Lawson lays out the main problems that organizational dualism attempts to address, explaining that the:

“concept of the ‘social’ and ‘political levels’ aims at clarifying confusion and mistakes in previous anarchist theory. The conflation of the two has led to not only theoretical, but organisational errors amongst other currents of anarchism, in particular anarcho-syndicalism […] The social level is where basic class struggle occurs. Struggles at this level are popular, wide ranging and mobilise significant numbers of not only the working class, but periphery and intermediate classes around immediate demands […] In contrast the political level is where individuals, organisations and parties operate with particular frameworks and ideologies, aiming to achieve particular goals.” (from “Foundational Concepts of the Specific Anarchist Organization”)

[…] it is not uncommon for already-existing groupings to act as blockades to both political organizing and popular organizing. They alienate people from revolutionary movements and prevent politics from getting specific enough. On the political level, this happens by limiting the debate and mistaking tactical agreement for ideological unity. All of this usually occurs without ever explicitly discussing strategy, some people even taking offense when certain militants attempt to take up the task. For this reason, we think that:

“[tactical] allegiance is insufficient for organizing revolutionaries because there must also be a place, in addition to the activism, for revolutionaries to cultivate militancy […] This avoids confusion and debate about fundamental positions in the future, making the established line easier to hold over time, something which is necessary when collaborating and compromising with a popular coalition.” (from “How do you say especifismo in English”)

[…] Beginning from the premise that tactics lead to other tactics, we can understand any use of a single tactic as the result of a distinction from a previous tactic and a move toward another tactic. For us, acting with strategy means connecting the movements from one tactic to another in a way that makes this movement as intentional as possible. A collective action could be a repetition of a previous tactic, or it could be drastically different from it. Either way, none of these small units of action serves as a strategy on its own. If only a single tactic is needed to successfully accomplish an objective, then the strategy would be to repeat the tactic a certain number of times, or to execute the tactic and wait for the eventual result, or even to wait and only employ the tactic if the situation does not develop the desired way on its own. This means that even the most simplistic and minimal conception of tactics requires strategy to inform the temporal aspect of action. When do we employ a tactic? When do we stop?

[…] Questions of strategy cannot be answered from the perspective of a single, fixed position in the struggle. Tactics themselves are rigid, sharp, and situated, whereas their employment can, and must, be dynamic. The political organization must persist through the complex multiplicity of crises and specific struggles that exist on the social level, and this must happen regardless of:

“[the] challenging reality […] that different sectors of society have vastly different needs. If a political organization aims to engage in different movements within society, these movements will require their own knowledge, study, theory, and strategy […] giving them the full respect and genuine effort that they deserve and require to become effective social forces. By organizing their activities into “fronts” of engagement, a specific group can stay acutely aware of its organizational capacity and its positionality within popular struggles.” (from “How do you say especifismo in English?”)

An absence of political organization leads to what may seem practical but are, in fact, overly simplified conclusions about how strategy and theory don’t really need to be discussed […] It is in this way that tactics are mistakenly understood as strategic positions. For people defending their own lowest common denominator forms of organization, critiques of tactics are wrongfully interpreted as ideological threats” [See: “El movimiento: A critique of tactical formalism in anarchist organization” by the I-5AF]

First grade notes on strategy

Let’s also quote from the First Grade Primer:

“[…] more engagement on the social level requires more organization on the political level, for developing both strategy and coherent ideology. It involves interrogating what we want together, over and over again, in order to refine and reinforce it.

Relevant political strategy must be concerned with the relationship between place and intentional, collective action. So, rather than only moving conceptually from the abstract to the specific, anarchist politics should always be in dialogue with their terrain of struggle because truly revolutionary politics are contextual, not idealistic. They do, however, have the objective of connecting actions to both anarchist ideology and theory in a way that produces better, more effective strategy. This process of improving strategy over time by testing it in practice serves as a way of problematizing and challenging dogmatic ideological assumptions.

[…] Anarchists are just as guilty as Marxists of thinking that all of their political work progresses the class struggle. And while groupings of tendency can function as well-organized intermediate-level orgs, they lack ideological, theoretical, and strategic unity. Organizations easily plateau in this form, without strategically deciding whether the objective is to develop more affinity or popularize their struggle. It’s not always clear how political these spaces actually are. So, we need to recognize the strategic value of groupings of tendency without getting over-excited, making ideological assumptions, and overstating their actual degree of unity.” [See: The North American Anarchist Primer “First Grade: Organizational Dualism”]

A kindergarten-level understanding of strategy

Finally, let’s quote from the May Document on the subject of strategy:

“[…] Strategy determines what an organization should focus on when interacting with different practical elements in a given moment. So, strategically developed theory helps an organization understand a particular problem from a particular perspective by establishing a connection between a given situation and the analysis of It.

[…] In especifismo, effective action has nothing to do with the typical “wins” of a political party or reformist movement. A common problem for mutual aid organizations is that it is difficult to consider what a “win” would look like since mutual aid is as much a part of daily survival as it is revolutionary action. There is no inherent way to win at mutual aid. For this reason, efforts like this demand strategy, or else they can retreat into counter-cultural aesthetics.

Strategy is as much about what an organization intentionally does NOT do as it is about what an organization does. The collective force of an organization is also found in its ability to say that it will not do something for strategic reasons, making clear that not all decisions are made based on ideology alone. This is especially necessary in mutual aid efforts which are easily motivated by a sense of guilt rather than a practical, collective strategy. We think that the force of strategic action can help us overcome the force of moral guilt.

[…] We agree with the FARJ that acting strategically involves an organization answering these three questions:

1. Where is the organization right now?

2. Where does it want to go?

3. How is it going to get there?

When an organization responds to these questions, the answers have a “shelf-life” forcing the regular reproduction of both the (more contextualized and responsive) “micro” forms of strategy and the (more general and permanent) “macro” strategy.

[…] Social work should be done in an effort to continue working toward popular “wins”. It is an opportunity for the political organization to seek feedback from other organizations and militants from the social level. This input should be factored into the evaluative processes of the political organization as an integral part of the reflections that aim to shape ethical interactions.

[…] it is important to do social work that supports rank-and-file participants who are placed on the peripheries of power both by leadership and by dominant ideological forces. Nevertheless, as we have said, longer-term strategizing necessarily happens at the political level and requires ideological and theoretical unity. This means that, politically speaking, “checking-in” consists, not of assuming unity, but instead, of doing the real work to form it. […] overlapping political lines can be difficult to discuss with some people and organizations, but the militant drive to do so is the political force behind especifismo. By presenting a well-articulated political line, people can learn about anarchist political strategy and determine their relationship to it as individuals isolated in struggle or as members of their own political organizations with their own strategically determined criteria for cooperating with others.” [See: “The May Document” from Militant Kindergarten]

Leading the march to nowhere

We see a problem with social-level struggles where everyone’s invited to put on rose-colored-glasses and participate in any way they like, strategy not required.

For example, social media gives us a false sense of pace that we feel like we’re supposed to keep up with. This leads us to try to present complex ideas or meaningful sentiments in the form of cool and flashy infographics. But this confuses pedagogy and propaganda. And there are no shortcuts to learning, just as there are no shortcuts to social revolution.

We see a similar pressure coming from current events and election cycles that present us with short-sighted objectives and the feeling that we have to do things quickly, before an approaching deadline. These contexts are very inviting to cute rhetoric, current trends, and band-aids for structural problems, all of which are detours from the path to real emancipation.

It’s no secret that radicals, activists, and militants tend to do the same thing over and over again, or at least to talk about it incessantly. This allegiance to played-out discourses of the past isn’t only boring, it lulls us into familiarity and keeps us stuck in a loop. These dead-ends are related to the limited resources of our organizations and the financial demands of the weekly, seasonal, and annual needs of the community. What we’re saying is that mutual aid is a kind of loop we could get trapped in. It’s hard to simultaneously respond to an immediate crisis and to never-ending needs, all while continuing to make strategic advances on our long path to social revolution. We know that, especially at our current conjuncture, responding to a crisis with only mutual aid is a trap, a way of getting stuck, a way of falling back into our old habits, repeating the same actions as if we’ve learned nothing from the past. This vortex swallows up our efforts and reproduces the system. So, “charity” is like mutual aid that’s stuck in a loop of NGO’s, moralizations, feelings of guilt, personal responsibility, routine actions, tactics from other times and places, etc.

How do we make progress as we zigzag with the changing conditions?

From our discussions in Second Grade, it’s clear that we have to go on a deeper search for revolutionary methods and discourses relevant to our context. And this search cannot be satisfied with just one perspective or program that never changes.

When we read and study texts and manuals from other periods of history or from other contexts of struggle, we interpret this discourse as something relevant to the time and place where it was written. We don’t take it as dogma and don’t think that it will automatically be useful in our own context.

Revolutionary politics cannot just be a bunch of fancy rhetoric. And we don’t have time or energy to waste getting even more bogged down than we already are. We have to move forward and not just repeat ourselves over and over again because wasted efforts that don’t last won’t destroy the system. When we act without thinking, we inadvertently lead the movement to an unknown destination.

Even a successful tactic can have unforeseen consequences. Like the tires of a car, peeling out due to hitting the gas pedal too hard, too fast, applying too much torque on one militant or on one front of struggle, or on one station on that front, without enough power to back it up, this is the problem we’re facing.

“Slow down because I am in a hurry, the historical experience that aspires to real emancipation could say.” Quit making the same mistakes, it might tell us in particular…

To avoid endlessly repeating ourselves and reproducing the system, we have to look at our own context from the perspective of the oppressed classes. This ensures that our strategic line is developed from within the situation and not assumed to inherently be on the correct path to the “post-capitalist” society.

Especifismo is different from theories that attempt to discover the truest/shortest/most efficient path to the final objective. It’s also different from theories that attempt to define the final objective ideologically (dogmatically), rather than theoretically and strategically. They see the end goal as the historical destiny of the working class, rather than a project that could be co-opted and diverted onto another course. We believe that people make their own destiny. This means that the politics of especifismo are different from vanguardist politics that try to put people on a “strategic” path, rather than develop that path with them in dialogue and political-level struggle. Branding exercises, “sloganeering”, and marketing/sales are not what we mean when we talk about “doing politics”. But we’ve seen that, even locally, selling ourselves can become the main priority. This attracts uncommitted participants and misleads people about what they’re actually participating in. If we want libertarian socialism to be something on our horizon, we have to develop strategy collectively. This will only be possible because of historical conditions. So, if they’re not accommodating, we have to change the historical conditions through struggle against the ruling class, at whatever pace is currently possible based on a tripod of factors: need, organization, and revolutionary will.